In the age of utility, more than ever before, products are things we buy to be who we want and live how we want.

For brands, the hardest part of a connected universe is creating openings for prospects to connect on their own terms. That means satisfying the connect-me-now expectation of smartphones and tablets. Luckily, we’re just seeing the first swell of handheld platforms for m-commerce.

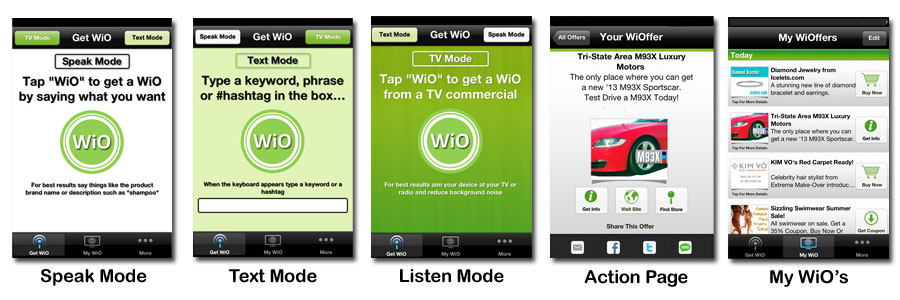

One of the pioneers in the second-screen space – what pundits are calling cross-platform engagement and activation – WiO (www.wioffer.com) is paving the way for marketers to turn their best (or at least their most expensive) creative executions – TV spots – into m-commerce vehicles. What’s more, it’s extending the cycle of brand offers to any medium and any time

WiO is an app that works on your smartphone or tablet device. Once you’ve got it, you can point your device at any ad bearing the WiO logo and a keyword to get instant offers for products, purchases, information, sweepstakes or other material the brand is offering nearby. You can do the same thing with billboards, print ads, and in-store displays showing the WiO logo and a keyword. Anytime you want, you can pull up the app, speak or type the name of a product or brand, or listen to commercials, and get any offers that are registered with WiO.

To hear WiO co-founder and CEO Andy Pakula tell it, WiO is taking marketers places that second-screen companies like Shazam and Get This don’t go today, and in the process is extending the state of the art of m-commerce in sustainable ways. What’s most instructive about his proposition is an emphasis on simplicity.

How did you first get the idea?

That’s easy – the escalating use of smartphones and tablets. We saw the possibility that marketers could finally get consumers to engage and activate with their best creative, on television, in a convenient way. If you make it easy for consumers to use, they’ll engage more. If you give them a reason to, they’ll engage more. More engagement means more activation. If you make the process simple, you’ll get more people to use it. The same goes for advertisers. You won’t get on their schedules if you make it too difficult. It has to be an easy process in every way, from technology to reporting to pricing. And, if it’s a new medium, the opportunity has to provide important research.

Is simplicity the greatest value?

Absolutely. That’s what made search engines like Google so popular: a simple proposition of people searching for what they want and advertisers buying keywords that people are searching. These companies didn’t have to produce additional content, and they could expand rapidly based on pure usage. We’re similar in that we’re the most flexible second-screen, cross-platform app. People can see something on TV they want, and they can immediately get an extension of that offer just from clicking or speaking into the phone, right down to the hyper local level. We’re making it convenient and simple for consumers to interact with advertising whether that’s TV, billboards, products on the store shelf, newspapers, listening to the radio, or even at a ballpark. We’re not just tied to TV like Shazam, and we’re not tied to backend cable systems like Connect TV. We allow consumers to engage with any of a marketer’s messages anytime and anywhere – their home, outside, at a friend’s house, in the office, at the beach, anywhere. The more people use it, the more they’ll come to trust it.

How is this simpler for marketers?

We’re actually allowing marketers to connect with consumers across all media from one source, creating a central place for offers. They can measure in real-time how they’re doing across media without having to rely on multiple media companies for implementation, reporting and tracking. Marketers don’t want to spend a lot of money or overhead to get access to consumers across the board.

So what is your new firm actually selling?

We’re selling engagement and activation for marketers across different media and convenience and savings for consumers. Marketers can choose to use WiO the ways they want. We enable up to 14 different actions, including socializing their offers across Facebook, Twitter, SMS and email. All that gets generated dynamically. We’ve made it simple for consumers to engage quickly wherever they are, with just one click to call, buy, visit websites, get coupons, find the nearest location, save information and sale dates, register for movie premieres, enter a sweepstakes – it’s a very long list.

How do I have to change the way I think as a marketer?

Smartphones and tablets are the new consumer POS systems. Marketers need to start driving more activity to these devices. They need to be saying, “How can I take my most important media investments including TV and get people to engage and activate from them?” The world’s biggest marketers also need to think micro, not only, “How can I get consumers to engage?” but, “How can I deliver appropriate local activity to drive sales?” They have to prioritize convenience and make speed work for them. Offer something simple and localized on an ongoing basis. You’re going from a broad, national brand where you have to start thinking like Mom and Pop, and drive local traffic with relevant deals.

Are marketers making the leap?

Marketers and agencies are telling us WiO is a terrific solution, but they still need to understand how to integrate the app into their media plans. They want to do it right. And like any new medium, after a little bit of hand-holding, they’ll get it. This is a tool where you can get payoff today and build a new level of relationship with consumers going forward. It’s really a new way of doing business.

How are content companies reacting?

TV programmers are getting interested in WiO. Programmers are exploring how to use the app, because they’re getting requests from marketers. They’re seeing that WiO can provide a leg up when selling against competitors.

How would you sum up what WiO is in the world?

For consumers, it’s the ability to engage immediately with products and services they see advertised. For advertisers, it’s the ability to get activation from brand advertising, and monitor the action in real time across all media. That’s never been possible before.

Jan 03

2013: THE YEAR OF UTILITY

By Fred Pfaff and Art Cannon

Welcome to the year of utility in marketing.

Utility is the new measure of media. What can I do with it?

Specifically, what can I do with it that…

- Saves time?

- Increases my experience?

- Widens my connection?

- Gives me more control over my experience?

- Increases my social capital?

These are the criteria that determine the engagement that marketers are starting to measure in earnest.

- atmtx / Foter / CC BY-NC-ND

Why now? We’ve crossed the Rubicon in smartphone adoption. The world in your palm changes expectations, and those expectations raise the bar on marketing. Marketing will be judged by how useful it is, now that we have an unprecedented infrastructure of delivery and activation.

Utility imposes a shift in mindset and execution. It introduces a product focus to branding, a messaging ethos to technology, a direct marketing discipline to media, and a host of other major changes.

Above all, though, utility trumps sentiment. Ad giants have built a business on sentiment that falls a distant second in an age where I want to do something. In the year of utility, your marketing can’t just communicate your benefit. It has to deliver it, through mechanisms that let people experience the value in everyday life.

Over the course of the year, we’ll explore this topic here, through interviews and guest posts providing useful thinking on marketing you can use.

Dec 28

A TALE OF TWO KINGS

The great TV divide is one of programming and calendar.

by Art Cannon and Fred Pfaff

Today, TV columnist Ed Martin came out with his top 20 for 2012 (http://bit.ly/Ur47m6) today, and cable beat broadcast 14-4 (PBS had two winners, and didn’t count in that total). Meanwhile, Variety published Nielsen findings of an 800% spike in social TV (where audiences discuss program content in real time on social networks) this year.

That’s a neat encapsulation of the widening divide on air. Breakthrough original programming is predominantly on cable. Broadcast is winning with reality TV, whether that’s sports, conventions or contests – the stuff that caters to the people who yearn to participate in a shared experience, and therefore watch with one eye glued to their mobile device.

The TV programming universe is splitting between storytelling on cable and live experiences via broadcast.

One way to characterize the divide is programming and calendar.

On the programming end, the standard setters increasingly debut on cable. Not only do they set the standard, they kill the competition that doesn’t live up to it. Fox’s heavily promoted “The Mob Doctor” got whacked early in its debut season, largely because HBO already showed us Mafioso in track suits (“The Sopranos”) saying something stronger than “damn.” Similarly, “The Wire” and “The Shield” raised the bar on cop shows to the point where broadcast networks can’t compete. CBS scores with “Blue Bloods” because it’s more a family drama than a cop show.

That’s a long way from the Nineties, when “NYPD Blue” was redefining edgy drama on ABC primetime.

Cable nets can take a fewer, better approach to original programming. They commission fewer pilots, and they average fewer episodes per season – 10-13 versus 22-26 for broadcast – so there’s less pressure to pad storylines. As a result, more happens in an episode, and they can advance their characters faster.

The calendar helps, too. With fewer shows to pack primetime, cable nets replay their hits throughout the week – so they’re easier to catch live or DVR. What’s more, virtually every cable network is in your VOD library. There’s more chance for water cooler talk to translate into new fans now. Cable has evolved to a your-calendar mentality that fits the way we live, whereas broadcast maintains an our-calendar schedule that accommodates its volume of programs.

What’s working in broadcast primetime? Reality, whether that’s a big game, the presidential debates, or “The Biggest Loser.”

Nothing draws a wider audience than the biggest sporting events. For most viewers, taped sports is like flat soda – the elements are there, but the pop is gone. The pop is the suspense, so once the game is over the thrill is gone.

Life contests, from singing (e.g., “The Voice”) to scrambling (“The Amazing Race”) to transforming (“The Biggest Loser”), continue to grow on a related principle. People want to be part of the action when they’re pulling for their favorite contestant.

Reality is also the stuff of social TV, which looks to grow continually as more people seek to participate in the building of an experience (and as more people are attracted to sharing as the ultimate experience, where the program itself provides personal social capital)

Indeed, a yearend wrap by social TV monitor General Sentiment (http://bit.ly/UyzHzt) reveals that 10 of the top 15 social TV events of 2012 were news or politics-related. Leading the list in social media interactions were the presidential election (17.4 million), Hurricane Sandy (9.4 million), and the second presidential debate (7.6 million). Big events also tipped the social scale in entertainment, led by the London Olympics Opening Ceremony (7.2 million) and the Grammy Awards (6.8 million).

The future of TV is a tale of two kings. Cable is the new king of storytelling, whereas broadcast remains the king of live experiences.

Sep 25

RUNNING AGAINST THE CROWD

This post, co-authored by Steve Ennen, president of Social Strategy1 (www.socialstrategy1.com) and co-founder of The Wharton Interactive Media Initiative, was first published August 29, 2012 on Adage.com (http://bit.ly/TvfMg6). Since then, New York Road Runners has amended its New York Marathon baggage policy – offering participants a choice of baggage check or quick exit (a fleece-lined poncho instead of checked baggage) – and stepped up its pro-active communication with a membership of well over 100,000 people. NYRR president Mary Wittenberg told me this weekend that 80% of participants elected the quick-exit option, which underscores the point of our post. To wit, it’s not about the bags. The uproar over a sudden policy change had to do with the expectations of communication in a digital age.

Outcry against a one-directional New York Marathon mandate shows how marketers still undermine their own communities with analog actions in a social media era.

By Steve Ennen and Fred Pfaff

On Thursday, August 23, 40,000+ people entered in the New York Marathon (November 4) received a startling wakeup call. In an email letter, the CEO of NYM organizer New York Road Runners informed participants that, starting this year, there would be no bag drop at the marathon. For participants, that means personal items, including dry clothes, will not be transported and available for pickup after the race. The letter and an accompanying list of FAQs explained the efficiencies this would create for NYRR and its supporting cast of police, volunteers, and Parks employees; and it made an attempt to assuage participants by saying there would no longer be a long walk and wait for baggage after a grueling 26.2 miles (a cause of complaints in past years).

Hours later, NYRR members (active and inactive, easily more than 100,000 people) got the letter. Within minutes of each email, social media networks lit up with complaints – and, importantly, snipes at NYRR. Almost instantly, another 34,000 heard the news via Twitter; Facebook runners joined in the discussion to the tune of tens of thousands; and the issue is still running through the blogosphere. By Monday morning, 1 million people had heard of or chimed in on the move. The conversation had gone global; most of the sentiment was resentful of the move (as measured by social media monitoring technology); and, already, a variety of service suppliers are taking to Twitter to offer solutions. Meanwhile, the decision and the outcry made headlines from Running Times to The New York Times.

For the folks complaining, it was the last straw in a series of changes NYRR had made to their races without consulting the community. The backlash drove a clear drop in goodwill for NYRR. A few choice comments from social media: “asinine,” “pretty weak for how much you pay.” “NYC was never a favorite…I bet the elites will have their bag well cared for.” The uproar grew louder Tuesday when a blogger posted that NYRR had consulted several supporting organizations privately back in January and simply closed ranks when the no-baggage idea was soundly rejected (http://bit.ly/PLHw22).

The point of the story for marketers is threefold. First, people expect transparency, consultation and collaboration in the Internet age. At the very least, they expect advance or engaged communication on an issue that affects the community. For better or for worse, they will extend this unwritten contract beyond the social realm. Second, marketing can’t fulfill on the brand promise without support from the complete enterprise. Third, classic operations-first mentality doesn’t fit a social media world. While we’re both runners and Fred’s a NYRR member in this year’s NYM (not keenly affected by the policy, being a Manhattan resident), our fascination is with the marketing crossroads.

It’s not a top-down world anymore. Community engagement, and the sentiment that springs from it, bucks the expectation of corporate management. And when the community is enthusiast-based, the resistance to one-way communication can be fervent. The analog playbook says management decides what best for the operation. For NYRR, there’s tremendous efficiency in doing away with the collection, carting and redistribution of personal items. However, that’s less important than nurturing the running community. The social playbook says management does what is best for the wider enterprise, including communities in brand decisions.

A community isn’t a database. This is where mindsets collide. NYRR is demonstrating the perils of a database mentality in which contacts are message recipients, and the top only listens when there are complaints. With a community, what counts most is how you communicate – from when you prepare people for change to how you actually announce, explain and process it. It’s a simple matter of courtesy, but a tremendously important component in social decision-making.

Given that its brand exists for and because of runners, a community whose connection is passion, why wouldn’t NYRR connect, listen and response to the community before a crisis point? Ironically enough, the New York Marathon depends on thousands of volunteers, most of whom are dues-paying NYRR members.

Community comes with a cost and a responsibility. When courted with respect, a brand community self-perpetuates. When dictated to, it revolts. Now that companies are beginning to crowd-source key attributes – ideas ranging from message to customer service to product development – the most avid online consumers are becoming conditioned to inclusion. That expectation is setting a new brand standard.

Social washing isn’t coming clean. In simply providing an email and a hashtag (#nyrrlisten) for complaints, NYRR did what a number of organizations do now: Use social media as a catchment for scorn. Relegating social to the aftermath belies the power of the channel and opinions of the group. The approach rings as hollow as, “You’re one of our most valued customers…current hold time is 30 minutes.” By contrast, soliciting feedback first, then explaining the final decision, shows people they’re valued.

Marketers need to listen and engage before the crisis points in order to activate one-to-one brand ambassadorship on a global scale. Admittedly, this will take most companies out of their comfort zones, as it has with any quantum leap (consider electricity, oil-fueled transportation, and space travel). Ultimately, the social media generation will force business to make media everyone’s job, with a shared community connection from the start.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This post comes courtesy of FPI lead strategist Art Cannon, whose intellect is too mighty to be traded for cider (even if it is from Heineken). Watch this space for guest posts from Art and others in the coming months, as we stretch our content legs.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By Art Cannon

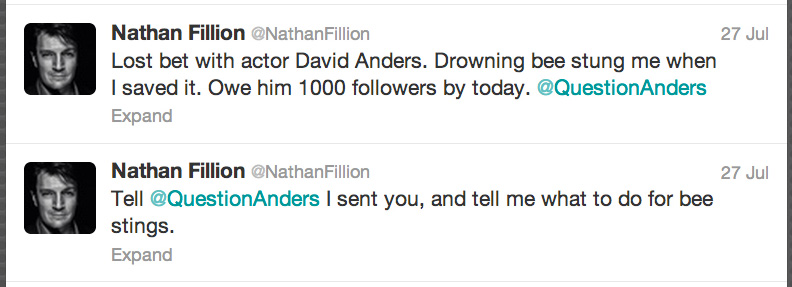

While I was catching up on Twitter and settling in for the weekend last week, I got the following update from actor Nathan Fillion (not that we’re buds, I just loved the show Serenity is all, so he gets a follow):

I can’t decide whether to be excited or upset by Mr. Fillion’s bet (it more than worked, as he later reported that @QuestionAnders netted 2,000 followers from it). All I know is that Nathan broke the Social Contract, or at least laid it bare for us to examine for a moment.

Social media’s fundamental promise to those who have embraced it (and the inevitable social marketing that’s followed its users, since someone’s got to pay for this party) has been premised on two things: intimacy and immediacy. In a single tweet, Nathan managed to turn his followers into a commodity. He packaged us up as an audience to monetize, with little regard for valuing our composition.

I feel like I just watched the scene in Almost Famous where Penny Lane was horse-traded away for $50 and a case of Heineken.

Speaking of Heineken, they’re taking the precision approach to social currency. They calculate that social media fans of their brands are worth an additional 80 bottles/$308 sales per fan, annually. That translates to an additional $25 million+ for their Bulmer’s cider brand in the UK. They obviously have no compunction about putting a price on our friendship (though I suspect it’s being calculated in the name of budget justification).

Together, actor and brewer have framed the extremes of an essential valuation – from throwing around their social currency literally to measuring exact ROI. These extremes raise questions about our social media expectations on three levels.

Transparency – This ties into the intimacy dimension of the Social Contract – that we’re in on the joke, and that we can see who benefits when we interact with brands. In each of these examples, this transparency remains true. Nathan explains the premise for his request. In Heineken’s case, if you haven’t figured out in your own life that “friending” a consumer product increases loyalty and might increase sales, well, you just come sit over here by me.

Appropriate measurements & precision – Fillion lost a bar bet, and pulled a figure out of his backside as a reasonable recompense for the winner, while Heineken is trying to quantify fan value in order to keep their efforts rolling, while selling some cider in the process. One side looks casual and carefree, the other almost a little too precise. I’d be wary of anyone who can’t ballpark what social marketing is worth to a brand in the marketing mix, but I’d be just as skeptical of someone who has it figured out to the penny.

Who retains the value of an audience? – What’s fascinating is that both these audience valuations work, within the confines of social media. Even better, each respective brand gets to retain most of the value of their audiences, with little lost in in friction/fees to Twitter and Facebook.

Now, here’s the space to watch: As Facebook scrambles to make up with Wall Street, and Twitter reins in its experience yet again (to prevent itself from becoming a dumb pipe), will this economy of sharing remain so efficient? If we catch Twillionaires like Nathan Fillion trying to pay for gas in followers, we can be sure that another shoe’s about to drop.

This is a repost of an article we wrote for Marketing Daily, published July 25, 2012 (http://bit.ly/Omr5Gm).

Marketers need to take a longer view to win with the short form.

by Fred Pfaff and Art Cannon

We’re entering an era of atomic messaging. As Twitter’s brevity and mobility attract more users along its inexorable march to a billion, the marketing community is realizing that short is smart. Long form media aren’t doomed, but the engagement bar keeps rising with respect to intensity and immediacy. As radio served notice to print, and email made direct work harder to stay relevant, now social (with an emphasis on short) is telling all media channels one thing: Get to the point.

This urgency reignites a time-old problem for marketers. It’s easier to string together reactive communications than it is to structure an integrated campaign. But that integration is precisely what the Great Twitter Rush will impose on marketers. Because you can’t establish a broader, more thoughtful context in a 140-character communication, you have to have established the base already. And short form messaging needs to lead people back to the brand itself.

Said another way, Twitter needs to be integrated into a pre-thought strategic construct. Winning with it is ultimately a matter of experience integration. You have to build for the experience, and build experience upon experience. Tweets can lead to treats or treatises, depending on what’s appropriate for the brand. The key is that they lead to something.

Twitter is built for speed. Speed can still work for thoughtful propositions, provided the speed creates meaningful connections. The faster we go, though, the more grounded we need to be. Optimizing for Twitter isn’t about what you do on it, it’s what you build from it.

With each tweet, the attraction is in the offer. Sometimes it’s self-encapsulated, an iota of information of value for a brand’s fans – in which case the context comes pre-established (they’re fans). Most times, it points to some other engagement content that leads to another, and another, and another. And that’s where the forward vision and infrastructure come in.

To get to meaningful engagement, marketers need to plan for the entire molecular chain upfront – in ways that leave room for reaction, of course – so the short pop that shows up in someone’s feed leads to a series of engagements that accumulate meaningful mass (and maybe even a sale or two).

Think of it this way: We’re used to building beaches by the truckload. Now we have to build a beach one grain of sand at a time. So it’s even more important to keep the beach in mind.

This is why contest programs that use Twitter on the front end work well. There’s a complete – sometimes elaborate – system in place to usher people through the chain. The thinking’s been done in advance. Twitter is the lead on top of the program. Another example, in B2B, is research, which allows for Twitter front end to lead to capture pages for executive summary, full report, comments and requests for presentation that can be followed up by sales reps. Both are reward-based. One reward is a prize, the other is intelligence.

When you don’t have an offer within a natural chain, it gets harder to integrate the short form messaging. The grains need to be sprinkled with the beach in mind. By the beach, we mean the overall experience of the brand. We’re talking your role in people’s lives and aspirations.

In practice, that means principles first. What kind of short form content is authentic to the brand? What is on-role? What is on-permission with your audience? You can’t prescribe the language, you can only establish the principles, so everyone is grounded in why you’re using the platform. If Twitter’s in your mix today, does it reflect your core message and connection? Hint: If you have a roomful of interns cranking out tweets, you’re not there yet.

Twitter and its cousins will work their way into the marketing surround one program at a time. As they do, marketers must learn to generate power in context: the creation of a chain of experiences that’s triggered by something as short as 140 characters.

Jul 20

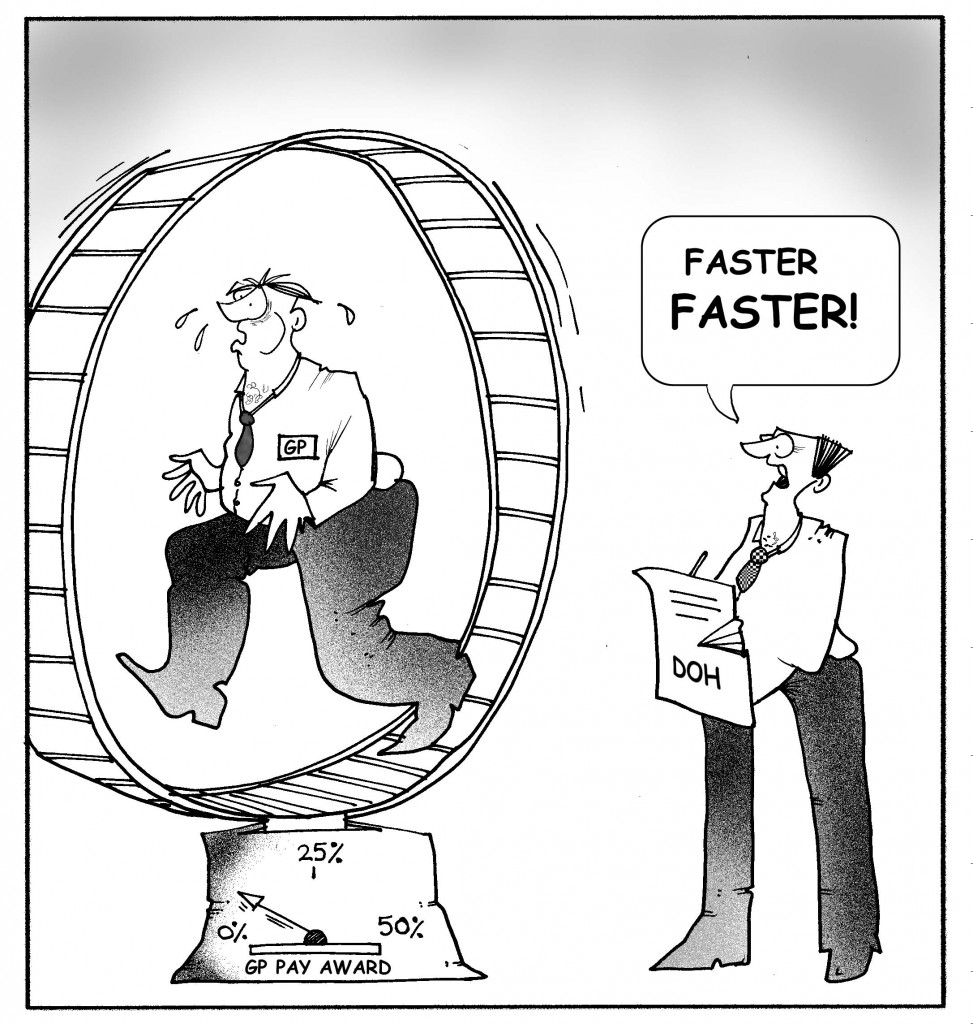

MOTION IS NOT MOMENTUM

Back in 1993, when I started Fred Pfaff Inc., my dad gave me his reaction to a firm I’d free-lanced for on my way out the journalism door. “All hustle, no strategy,” he said. “And nobody there can write.”

What Dad noticed was a trap that PR falls into today more than ever: mistaking motion for momentum, which I’ve come to call the Big Hustle. Clients fall into this as readily as agencies, particularly as the world spins faster. They end up putting a premium on action – any action – and lose the message.

One reason for this premium on action is there’s frequently no linear relationship to results. Another is that the amorphous nature of the activities that PR requires – clients don’t see most of the work – breeds pressure to provide something tangible, from constant update charts to a whelm of press releases. “At least somebody’s doing something,” says the CEO who’s suspended disbelief just long enough to let the CMO run with an agency.

Still another cause of this weakness is PR’s heritage of reaction. Journalists want what they need at the moment, which is increasingly a pithy comment in a flash for the 100th post on Facebook’s latest move. So we get PR hordes running, shouting, and tumbling for a mention that’ll satisfy the client’s management, board and investors, all of whom now know to check Google Alerts for mentions of the company.

Ironically, the Big Hustle never really gets you anywhere with media; you become a gnat that reporters and editors swat away, and you become indistinguishable. It never really positions your client, because it sacrifices the story that’s crucial for the commentary that’s expedient. It burns you out, unless you’re truly the hyper-kinetic type. And it thwarts shared accomplishment because there’s no clear end point, only forever running to react.

The Big Hustle violates three tenets of communications:

- Not all messages are created equal.

- Not all exposure is created equal.

- Exposure is a means, not an end.

I’ve run into Big Hustle syndrome in B2B lately as clients and PR firms try to keep pace with the explosion of channels and speed of information. Updates intensify – sometimes thrice weekly – while releases predominate and reactive viewpoints get rushed out the door, sapping the energy of client and firm alike when it comes time for creating messages of their own. Predictably, the Big Hustle overplays inconsequential events and reactive opinion, and misses meaningful insights at the core of the business. By meaningful insights, I mean the things that architects of change can point to as barometers and models to move business forward.

Momentum isn’t how much motion you can muster. It’s how much traction and reaction you can generate. It’s actually getting somewhere. Increasingly, that’s a matter of patience and precision: investing the energy to plan, focus, and build on the communications that really matter.

Jul 09

HALF MEASURES

Just read a story on BizReport (http://bit.ly/NB7qCb) that Simon & Schuster is putting QR codes on the backs of new books. Their goal is to get people to visit the company’s and the author’s websites and sign up for an email newsletter.

Oh, cool, QR codes on books now. But BizReport writer Helen Leggatt called the real question: Aren’t you doing something more, or at least more in keeping with the spirit of how people use QR codes? Leggatt writes: “When people scan a QR Code they want something a little more stimulating and rewarding. Had the publisher linked the codes to free additional content relating to the book, say a free sample chapter or two, or even a competition to win related products, it could see more success.

This is the same thing that’s happening in hyper local mobile marketing, where campaigns underperform because marketers don’t know how to design for real consumer interaction. Like Simon & Schuster, they’re thinking of their own efficiencies (it’s a lot cheaper to sell books to a subscriber base that demonstrates interest in particular topics, authors, etc.). That’s a trap.

We use technology for a purpose. Before putting technology to work in marketing, we have to define the usage chain and grease it entirely. Otherwise, we’re guilty of half measures that can backfire on many levels. Consumers don’t get what they want, so they drop off. And some get annoyed, forming and sharing negative opinions of the marketer.

Digital interconnection means we need to think through to the end of the usage chain. Brands have to provide value at every step if they’re to keep in step. Programming meaningful experiences throughout the chain is the next frontier. We’ll all get there faster if we think of our users’ efficiencies, not our own.

Jun 20

THE SIN OF SYNERGY

by Fred Pfaff and Art Cannon

“With increased resources and access to new geographies, our partnership with WPP will fuel the next level of energy, excitement and opportunity, delivering innovation and creativity at scale.”

– AKQA founder Ajaz Ahmed in the press release (http://bit.ly/Mgz4WN) announcing WPP’s acquisition of his agency.

The big question isn’t what happens to AKQA, it’s whether holding companies will ever create the synergy that rollups promise.

Usually, the synergy promise dissolves into partisanship, expressed as internal competition and unclear roles. The assets don’t readily get combined for sales and delivery of client programs; referrals often happen because they’re part of the bonus plan (a holding company agency exec once told Fred this point blank). And when the big teams do get put together, they’re uber-expensive, special projects instead of the ramp to a new normal. And so the story has gone in the ad space rollups since I was a beat writer and Art was a technologist.

The crux of the problem is this: Holding companies are good at using new acquisitions as BD channels and marketable capabilities. They aren’t built for integrating the knowledge quickly. That’s a missed opportunity, because so much of the prime talent is getting concentrated where it can’t really create the next-gen models.

As one of our clients tells us constantly, adding capabilities to a company or its executives doesn’t necessarily lead to capacity. That’s particularly true with respect to higher-order thinking. And Ad Age’s Michael Learmonth (@learmonth) made the point this morning that “when you buy an agency, you’re basically hire-acquiring everyone there. Client relationships, expertise, but no tech.” Another way to say that is acquisitions add talent but don’t build tech capacity.

There’s more potential to scale technology than, say, media savings (especially since any network exec will tell you privately they can’t afford to give the best deals to the buying Behemoths). Yet every new M&A deal that promises the integration of a new capability or technology doesn’t seem to happen any faster for the acquirer than for the industry itself.

Because holding companies are piggy banks, not think tanks.

If the ad biz stopped to think, it just might wish they were the other way around.

May 01

BEACHED SALES

Pulling marketing and PR can leave salespeople pinned down.

When colleague Jim Elliott asked me to address the tendency he’s observing to cut back on marketing, I wrote this for the current issue of “Ads & Ideas,” the newsletter of James G. Elliott Co.

In every time of doing more with less, it’s tempting to cut back on marketing and PR, thinking that more sellers in the field is the most efficient way to advance the business. Nothing happens without sales, goes the argument, so more feet on the street will identify and seize more opportunities. We’ll add the other fun stuff when we’re flush again, but for now we need to buckle down and pound the pavement.

There’s a hole in that plan. Salespeople are not efficient marketing vehicles. In fact, the tighter budgets get, the more inefficient they are. The reasons have nothing to do with the role or importance of salespeople; they have everything to do with the nature of sales in the media business.

First, buyers are overworked, underappreciated, and inundated with pitches. The impression they already have of a publication goes a long way toward setting their minds on any single opportunity; and 15 minutes with a sales rep isn’t likely to change that.

Moreover, salespeople can only make one call at a time. That means without marketing and PR support, publishers have to market one sales call at a time. Making things tougher still, more time and effort goes into each call today. Sellers can’t schmooze the day through either; they have to plot credible connections for clients within their publications.

Reps need content, too. Reminder emails don’t work if all you’re reminding a buyer of is that you want her business. You need to have something to forward the action. Nothing does that quite like substantive media coverage. At a time when anyone can post a blog, a nod from respected media (whether it’s a story about or by a publisher) signals legitimacy.

Once upon a time, when there were dozens (not thousands) of magazines and the rotary dial was high tech, there were hours for bonding over steaks and martinis. Today, the people who do the most hands-on buying barely leave their desktops during the day. They’re young, smart and under the gun. They need some reason to take a meeting to begin with, and the credibility had better come from someone other than you.

RFP (aka, Really Fast Please!) fire drills leave no time to sell in person. They’re 24- to 72-hour scrambles to propose elegant solutions to client marketing briefs. You won’t get the RFP if you’re unknown, and there’s no way to build a reputation in an online response. For that, you need messaging and momentum over time.

One publisher’s tale of two cities says it all. In the morning, he met with a client who knew his magazine well and read it cover to cover. They talked for an hour, mapped out a yearlong content program, and booked a dinner weeks out to extend the conversation. In the afternoon, the publisher flew to see a media buyer who didn’t know his magazine. He spent 15 minutes trying to get her up to speed, while she stole glances at her iPhone. They never got to specifics. His time was up before he could establish a basis for conversation. He got pinned down on the beach.

The best air cover is establishing the magazine’s point of view at the industry level. What it stands for, why it matters, why its audience is attracted. That’s where marketing and PR people come in. The same reasons that make it tough to get a buyer’s attention let alone time—too much information, too little time—make it incumbent on media to market the ideas, people, tools and accomplishments that make them matter, and do it in more focused ways. Establish relevance and credibility before a meeting, and a rep can focus where “yes” lives—specific ways your audience can move the buyer’s brand.